DNA polymerases

Many applications with fundamental importance in modern molecular biology and biomedicine, including the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and whole genome DNA amplification (WGA) as well as some of the state-of-the-art DNA sequencing technologies, would not be feasible without the advances made in characterizing DNA polymerases (DNAPs) during the last 60 years. Furthermore, the development of WGA at the single-cell and single-molecule level has contributed to some of the most recent breakthroughs in our knowledge of different complex biological systems: from microbial ecosystems, shedding light into the microbial dark matter, to human disease, enhancing the sensitivity to detect genetic variants and mutation profiles of individual cells in a tissue or tumor and changing paradigms in early diagnosis of cancer and genetic diseases with non-invasive genetic tests.

DNAPs are enzymes that synthesize DNA, by copying a pre-existing parental DNA molecule. Thus, they are responsible for preserving genetic information by replicating and repairing nucleic acid molecules in the cells. Their structure resembles a half-open hand, comprising the palm, thumb and fingers subdomains, which are arranged as a right hand in most of the DNA polymerase families (A, B, C, D, Y and RT), whereas members of the X family can be considered as left-handed. The single-subunit DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (DdRps) that are related to phage T7 RNA polymerase, and viral RNA- dependent polymerases (RdRps) also display a right-hand folding. A common mechanism and evolutionary origin for DNA and those RNA polymerases have been often suggested (Steitz et al. 1994, Koonin 2006, Monttinen et al. 2014); on the other hand, bifunctional primases-polymerases from archaeo-eukaryotic primases superfamily (AEPs) display an RNA-recognition motif fold with very distant similarities with DNA polymerases, suggesting a convergent evolution mechanism (Iyer et al. 2005, Guilliam et al. 2015).

PolBs

Among DNAPs, family B DNA polymerases (PolBs) have been suggested to be the most ancient group of DNA polymerases (Koonin 2006) and were usually divided into two groups (Filee et al. 2002): RNA-primed (rPolBs) and protein-primed (pPolBs). The rPolB group comprises mainly replicases devoted to accurate and efficient copying of large cellular and viral genomes, whereas pPolBs are exclusive to viruses, like Adenoviruses or bacteriophages from podovirus and tectivirus families, and self-replicating mobile elements with moderately-sized linear genomes (<50 kb) (Kazlauskas and Venclovas 2011, Krupovic and Koonin 2015).

New pPolBs and new DNA replication models

Biochemical characterization of new PolBs and pPolBs beyond the classic models is very limited. However, the establishment of new models is required to explore the evolution as well as the potential of DNA polymerases. During the last years of Modesto in the Salas’ lab he and Margarita were lucky to recruit a couple of very good students that help to establish the Bacillus thuringiensis virus Bam35 as a new model for DNA replication. Like the virus Φ29, largely studied by Prof. Salas and her co-workers, Bam35 has a double stranded linear DNA genome, capped with a terminal protein on its 5’-ends.

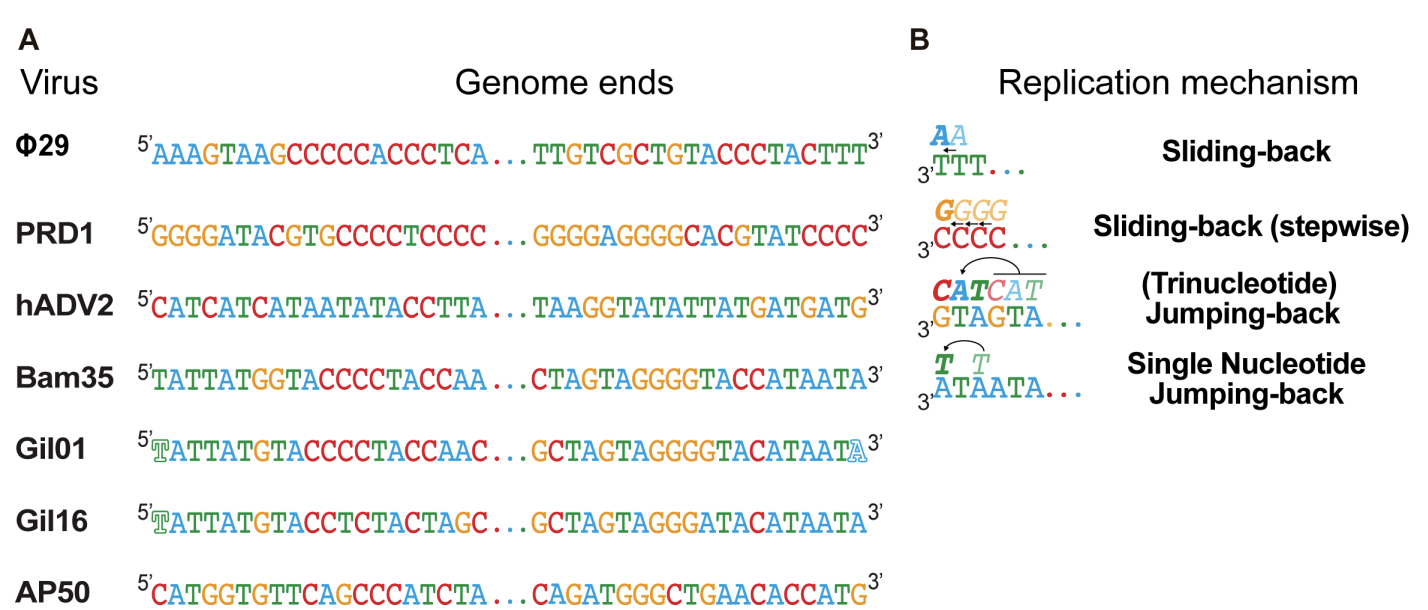

In two consecutive papers, Berjón-Otero et al. 2015 and Berjón-Otero et al. 2016, the main characteristic of Bam35 DNA replication machinery were revealed. Briefly, Bam35 pPolB is a highly processive replicase endowed with translasion synthesis capacity opposite to abasic sites. Addtionally, full-length Bam35 TP-DNA can be replicated using only the viral TP and DNA polymerase and genome replication priming entails the TP deoxythymidylation at conserved tyrosine 194 and that this reaction is directed by the third base of the template strand. the genetic information of the first nucleotides of the genome can be recovered by a novel single-nucleotide jumping-back mechanism. Given the similarities between genome inverted terminal repeats and the genes encoding the replication proteins, we propose that related tectivirus genomes can be replicated by a similar mechanism, although replication of more distant genomes undergo by different process.

piPolB

In collaboration with Patrick Forterre and Mart Krupovic (Pasteur Institute), we reported a third major group of PolBs, previously overlooked, named primer- independent PolBs (piPolBs), which display templated, de novo DNA synthesis capacity (Redrejo-Rodríguez et al. 2017). Contrary to RdRPs (Luo et al. 2000, van Dijk et al. 2004), DNAPs were believed to be unable to initiate replication de novo, which could be only partly justified with incomplete arguments, like the existence of hindrance impediments of dNTPs as compared with NTPs, the requirement for major protein structural modifications, or incompatibility with the proofreading activity (Lipps et al. 2003, Monttinen et al. 2014). Thus, the discovery of piPolBs dismisses those arguments and breaks the long-standing “primer rule”, a dogma in the field for 60 years, that stated that DNA polymerases required a pre-existing 3’-OH end to anchor the incoming nucleotide.

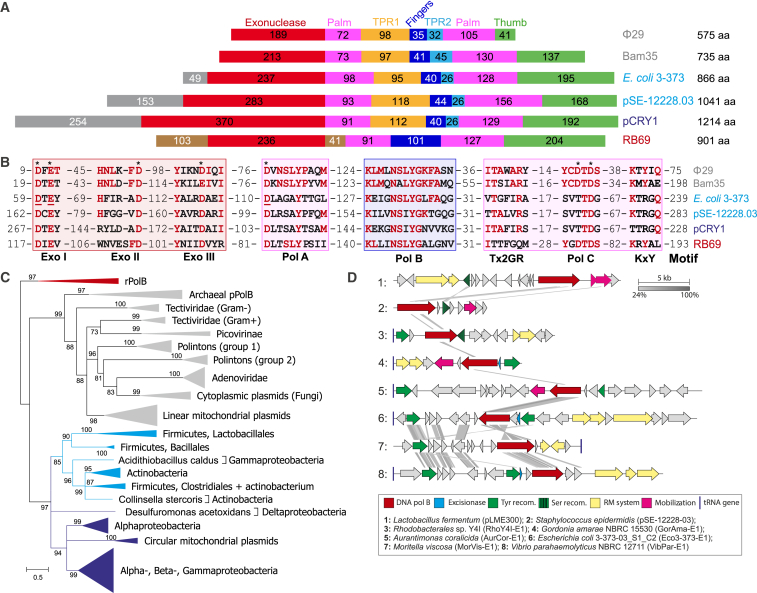

The evolutionary relationship among the three PolB groups is unknown and it is thus unclear whether the putative ancestral enzyme would have employed a primer and its nature (protein or RNA). Available phylogenetic analyses suggest that pPolBs and piPolBs might share a common ancestor (Figure 1C). Both groups, pPolBs, and piPolBs share the presence of specific subdomains, named TPR1 and TPR2 (Figure 1A), which were originally described in bacteriophage Φ29 pPolB (Φ29DNAP). TPR1 is required for the DNAP interaction with the TP and the DNA template strand, whereas TPR2 endows pPolB with the processivity and strand-displacement capacities (Salas et al. 2016). Indeed, the presence of TPR1 and TPR2 motifs have been usually a hallmark of pPolBs, which, provided that TPs sequences are usually not conserved, leads to prediction of a protein-primed DNA replication mechanism for a number of viruses (Peng et al. 2007, Fischer and Suttle 2011, among others) and self- replicative integrative genetic elements (Kapitonov & Jurka 2006), yet without experimental characterization of those DNAPs.

The piPolB-encoding genes are the hallmark of a new group of self-replicating mobile genetic elements (MGEs), that we named pipolins (for piPolB-encoding mobile element). Pipolins are integrated within the genomes of three highly diverse bacterial phyla (Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria) and are also carried by mitochondria as circular plasmids. Multiple sequence analysis (MSA) showed that piPolB share exonuclease and polymerase motifs of PolBs, albeit with notable variations within the PolC and KxY motifs (Figure 1B).

Escherichia coli piPolB promotes survival of persister cells after exposure to DNA crosslinking agents

Previous results from our lab indicate that this polymerase might provide an evolutionary advantage by increasing persister survival rate possibly by their interaction or collaboration with DNA repair mechanisms against genotoxic agents. Our results indicate that piPolB does not contribute to resistance against mitomycin C (MMC) or nitrogen mustard but to persistent survival, and that the protein expression is induced in the presence of distinct DNA replication blocking agents. While a mutant lacking piPolB (ΔpiPolB) showed reduced persistent survival compared to the wild type strain, the complemented ΔpiPolB+piPolB strain presents similar persistent survival ratios to wild type. Overall, our results support a biological role of piPolB in DNA damage tolerance and suggests its possible collaboration with DNA repair pathways such as SOS response. We propose the study of piPolB participation along other DNA repair mechanisms through epistasis assays. Finally, the biological role of piPolB and its wide distribution among diverse bacteria paves the way for future research lines towards the development of new treatments against resistant and persistent pathogens.